1965~ - Daido Moriyama

Weekday 11:00 - 20:00

Saturdays and Holidays 11:00 - 18:30

Sundays and Mondays Closed(Except for 2013.7.15)

Entrance Fee 800 yen for over 18

commentary

森山大道――ラビリンスの旅人

飯沢耕太郎(写真評論家)

1960年代後半以来、森山大道の写真を見続けてきた。最初は『アサヒカメラ』か『カメラ毎日』の写真ページの図版だったと思う。彼のページだけが、黒い闇の粒子でびっしりと覆い尽くされているような、異様な触感を備えていたのを覚えている。

それから写真集、写真展と、何度となく彼の写真の前に立ち、吸い寄せられたり、反撥したり、打ちのめされたり、溺れてしまったり、さまざまな感情を味わい尽くしてきた。いまや、コントラストの強い光と闇に縁どられた彼のモノクロームプリントの質感は、私の視覚的な記憶に骨がらみ食い込んでおり、常に既視感を呼び起こすものとなっている。時折、街の中でなまめかしい女性のイメージをプリントしたポスターや、ざらついた感触の物体などを見かけると、つい森山の写真の文体に翻訳して眺めていることに気づくほどだ。

そんなふうに、眼に馴染んでしまった森山の写真の視覚的な経験が、実はかなり特異なものであることに思い至る機会があった。2012年10月~13年1月に、イギリス・ロンドンのテート・モダンで開催された「ウィリアム・クライン+森山大道」展である。よく指摘されているように、森山のデビュー写真集『にっぽん劇場写真帖』(1968年)は、クラインの『ニューヨーク』(1956年)の強い影響を受けて制作されており、森山自身、クラインが「憧れの写真家」であったことを何度も語っている。にもかかわらず、展示会場を歩き回りながら、逆に二人の作品の違いを強く感じざるをえなかったのだ。

1956~64年に刊行された『ニューヨーク』、『ローマ』、『モスクワ』、『東京』という「都市四部作」を起点とするクラインの写真の世界は、そのアナーキーな見かけとは逆に実に論理的、構築的であり、ダイナミックに構造化されていた。ところが、そのクラインのパートを見終えて、森山の作品が展示されている部屋に入り込むと、まったく違った印象を抱くことになる。それはむしろ、観客が寄って立つ足場を突き崩し、体ごと宙吊りにしてしまうような、不穏な、禍々しい気配を発しているように感じられたのだ。

ここでは、その森山の写真の世界の特質を「湿り気」、「浮遊感」、「部分/断片化」という三つの角度から捉え直してみることにしよう。森山の写真を見ていると、梅雨時の、あの湿り気を帯びてじっとりと重たい空気に包み込まれているような気がしてくる。彼が好んで撮影する唇のクローズアップのイメージに特徴的にあらわれているのだが、ぬめぬめとうごめく水の層が、画面全体に浸透しているように感じる写真も多い。これまたオブセッションのように彼の写真に頻出してくる髪の毛や植物群も、あたかも水の中で靡いているように見えなくもない。

森山の写真の湿度の高さは、明らかに彼がアジア型のモンスーン気候である日本を主なテリトリーとして撮影しているからに違いない。雨や雪の多いこの地域では、風景は常に湿り気を帯び、写真家は水の中を漂うようにしてシャッターを切る。彼は自らの身体が液状化し、重力のくびきから解放されているように感じるかもしれない。そこでは、上下左右のどの位置にいるのかという方向感覚すら喪失してしまう。森山の写真のふわふわと宙を漂うような浮遊感、そこに写っている事物のとらえどころのなさは、そこから来ているのではないだろうか。

彼の写真を見ていると、そこに写っているモノや人間たちが、本当にそこにあった(いた)のか、あやふやに思えてくることがある。写真は、原理的に「そこにあった(いた)」ものを写しとる装置だ。さらに森山は基本的に「ストレート写真家」であり、画像の加工や合成などをすることはない(まったくないとはいい切れないが)。だが時折、森山の写真に写っている事物が、確固とした現実感を欠いたあえかな幻影のように見えてくるのはどうしてだろうか。現実と幻影とが彼の写真の中では常にせめぎあっており、時にその関係が逆転して、後者の方が支配的になることがあるのだ。

その傾向を助長しているのが、森山のあの魔術的な部分/断片化の手法ではないだろうか。彼の作品を見ていると、被写体の全体が完全に見えているものがほとんどないことに気がつく。人物の場合、顔が隠されていたり、胴体がまっぷたつに断ち切られていたりする。被写体の一部が、フレームの外にはみ出していることも多い。そのことによって、そこに写っている事物は、それが何ものであるのかがはっきりとわからないままに、ただの「物質」として目の前にごろんと投げ出される。

これも森山の写真によく登場してくるタイヤのイメージを見ていると、そのことがよくわかるだろう。それは人やモノを乗せて走るという自動車のメカニズムから切り離され、鉄とゴムでできた、暴力的といいたくなるような荒々しい感触を備えた塊として、闇の奥から出現してくる。それは既に見慣れたタイヤではなく、現実世界から切り離されて、夢の中で何度も出会うような、あやふやな、だが強く心を捉えて離さないイメージと化しているのだ。

森山の部分/断片化への固執をあらためて思い知らされたのは、2012年9月~11月に東京・銀座のBLD GALLERYで開催された「LABYRINTH」展を見た時だった。この1960年代から2000年代まで、彼が撮影し続けてきたフィルムのコンタクト・プリント(密着印画)を、そのまま大きく引き伸ばして展示した写真展には、彼が被写体に向ける眼差しのあり方がくっきりと浮かび上がってきていた。クローズアップが多いのは、被写体の全体よりもその細部へ、細部へと視線が吸い寄せられていくからだろう。しかも多くの場合、何回も連続してシャッターを切っている。時には、あの印象的な網タイツをはいた女性の脚のシリーズ(1986年)のように、フィルム数本分、同じ被写体をさまざまな角度から撮影している場合すらある。展覧会にあわせて刊行された写真集『LABYRINTH』(Akio Nagasawa Publishing)に、森山は次のようなコメントを寄せている。

「あのひとは、まだ見つからないので、旅をしているのです……」

人の日々は、迷宮に彷徨い、迷路を辿る、心と肉体の旅。

けっして、完成することなきジグソーパズル。

そう、森山の写真の仕事は、ひと言でいえば「ジグソーパズル」のピースを、倦むことなく作り続ける作業の蓄積なのだ。一見バラバラな断片が撒き散らされているように見えるが、それらを粘り強く組み合わせていけば、何か途方もなく巨大な図柄が姿をあらわすかもしれない。むろん、彼が正確に認識しているように、それはおそらく「けっして、完成することなき」ままに終わるだろう。それでもいいのではないか。一人の写真家が、自分の眼とカメラだけを頼りに、「迷宮」の中に踏み込み、摑みとってきたイメージ群は、いつでもわれわれを立ち止まらせ、震撼とさせる力を秘めているのだから。

Daido Moriyama

Journey through a labyrinth

I have been viewing Daido Moriyama's photographs since the latter half of the 1960s. From memory, the first examples of his work I saw were plates in a photograph section of Asahi Camera or Camera Mainichi. I remember that the pages featuring his work alone had a peculiar tactile quality, as if they were covered in grains as black as the dark of night.

Since then I have encountered his photographs any number of times in photo-books and at photography exhibitions, and have experienced just about every emotion imaginable as a result, including being attracted to them, repulsed by them, overwhelmed by them, and infatuated with them. Today the texture of his monochrome prints framed with strongly contrasting light and dark has knitted with and become ingrown into my visual memory, so that it triggers a sense of déjà vu. So much so that sometimes when I see a poster on the street featuring an image of a voluptuous woman or spot an object with a rough texture I find myself inadvertently looking at these things translated into the style of Moriyama's photographs.

There was one occasion in particular on which I came to realize just how peculiar the visual experience of Moriyama's photography, to which my eyes had grown completely accustomed, was. This was the “William Klein + Daido Moriyama” exhibition held from 10 October 2012 to 20 January 2013 at Tate Modern in London. As has often been pointed out, Moriyama's debut photo-book, Japan, A Photo Theater (1968), was heavily influenced by Klein's New York (1956), and Moriyama himself has said on a number of occasions that Klein is “the photographer I admire the most.” Despite this, as I wandered around the exhibition venue, I could not help but be struck at the differences between these two photographers.

Contrary to its anarchic outward appearance, Klein's photographic world, which emerged out of the "four city" series of New York, Rome, Moscow and Tokyo published between 1956 and 1964, was in fact logical and architectural and dynamically structured. However, upon entering the room where Moriyama's work was exhibited after viewing Klein's work, I got a completely different impression. I felt there was something disquieting or ominous about Moriyama's work, as if the ground on which the audience stood had been undermined, leaving them hanging in midair.

Here, I would like to reconsider the distinguishing characteristics of Moriyama's photographic world from three angles: namely, “dampness,” “a floating feeling,” and “sectionalization/fragmentation.” When I look at Moriyama's photographs, I feel as if I am wrapped in the kind of clammy, heavy air tinged with dampness that we experience during the rainy season. This is particularly the case with the close-ups of lips that he enjoys shooting, but there are many other photographs in which a glistening layer of water seems to permeate the entire surface. The hair and flora that appear often in his photographs, almost as if they are an obsession, also sometimes look as if they are streaming in water.

Looking at Moriyama's photographs, I sometimes begin to doubt if the things or people depicted in them were really there. In principle, photography is a contrivance that captures things that “were there.” Moreover, because Moriyama is essentially a “straight photographer,“ he doesn't process his images or use montage, for example (although I cannot say for certain that he has never used such techniques). This being the case, why is it that sometimes the things in his photographs take on the appearance of faint illusions devoid of a firm sense of reality? In Moriyama's photographs, reality and illusion are constantly struggling against each other, and occasionally the relationship between the two is reversed so that the latter becomes dominant.

One thing that may have fostered this tendency is Moriyama's almost magical technique of sectionalization/fragmentation. Looking at his photographs, one realizes that in barely any of them is the subject completely visible in its entirety. In the case of people, the face is hidden or the trunk is cut down the middle. Often a part of the subject is protruding from the frame. As a result, the things depicted in these photographs appear to have been flung in front of the viewer's eyes as simply "material," with no effort having been made to determine exactly what they are.

This should be clear if one looks at the images of tires that often appear in Moriyama's photographs. Here, the tires are detached from the mechanism of the automobile as a means of transporting people of things and emerge out of the darkness as masses made of steel and rubber with textures so rough one is tempted to call them violent. They are no longer the tires that are already familiar to us, but have been separated from the real world and transformed into the kinds of images that we have encountered again and again in our dreams, images that are vague yet leave a strong impression and refuse to go away.

Moriyama's adherence to “sectionalization/fragmentation” was brought home to me afresh when I saw the “Labyrinth” exhibition held at the BLD Gallery in Ginza, Tokyo from September to November 2012. At this exhibition, which featured a selection of the contact prints Moriyama shot between the 1960s and the 2000s that had simply been enlarged for display purposes, the way he looks at his subjects stood out more clearly than ever. The large number of close-ups is probably due to the fact that his gaze is drawn not so much to the whole but to details. Moreover, in most cases he releases the shutter any number of times without pausing. Sometimes, as is the case with that memorable series of photographs of his girlfriend's legs in fishnet stockings (1986), he even uses up several rolls of film shooting the same subject from various different angles.

In the photo-book published to coincide with this exhibition, Labyrinth (Akio Nagasawa Publishing), Moriyama makes the following comment:

“Whoever it is that I am looking for has yet to reveal themselves, so I continue my journey.

Each day is a journey of the mind and body through a labyrinth.

Sometimes my steps follow a path.

Other times, I find myself wandering.

Like scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, never finding resolution.”

That's right. In short, Moriyama's photographs are an accumulation of his work of tirelessly putting together the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. At first sight it looks like a scattering of disjointed pieces, but if he persists in putting these pieces together, perhaps some extraordinarily large pattern will reveal itself. Of course, as Moriyama accurately recognizes, this work is probably destined to end in “never finding resolution.” But perhaps that in itself is enough. Because the images this lone photographer, relying on nothing but his eye and his camera, has snatched after stepping into the “labyrinth” have the potential to stop us in our tracks at any time and shake us to the core.

biography

森山 大道

1938年、大阪生まれ。高校在学中に商業デザイン会社に勤め、その後グラフィックデザイナーとして独立。1960年22歳のとき、写真家・岩宮武二との出逢いをきっかけに、写真の世界へ飛び込む。翌年には上京し、細江英公のアシスタントを経て、1964年に写真家として独立。以後、『カメラ毎日』や『アサヒグラフ』『アサヒカメラ』などの写真雑誌を舞台に作品を発表し続け、1967年『にっぽん劇場』で日本写真批評家協会新人賞を受賞。

代表作に『写真よさようなら』(72)、『光と影』(82)、『Daido-hysteric』(93-97)、『新宿』(02) など。昨年末にはロンドンにあるTate Modernで『William Klein + Daido Moriyama』展を行うなど、日本のみならず世界中で精力的に活動し続けている。

Daido Moriyama

Born 1938 in Osaka. Worked at a commercial design company while attending high school, and then as a freelance graphic designer. Prompted by meeting the photographer Takeji Iwamiya, Moriyama plunged into the world photography in 1960, at the age of 22. He set off for Tokyo the following year, and after working as an assistant to Eikoh Hosoe, established himself as an independent photographer in 1964. His works appeared successively in photo magazines the likes of Camera Mainichi, AsahiGraph, and Asahi Camera, and in 1967, he received the New Artist Award from the Japan Photo-Critics Association for Japan: A Photo Theater.

Among his best-known photography collections are Farewell Photography (1972), Light and Shadow (1982), Daido-hysteric (1993-97), and Shinjuku (2002). He remains tirelessly active shooting and showing around the world, as evidenced in his recent exhibition "William Klein + Daido Moriyama" at Tate Modern, London.

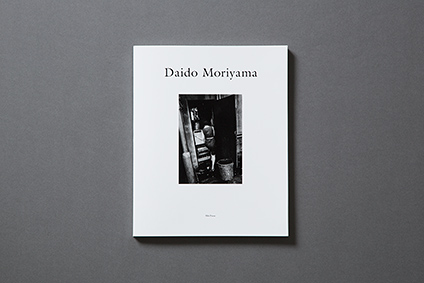

book information

森山大道写真展「1965~」の開催に伴い、写真集「Daido Moriyama」を出版致します。氏にとって、街は一つの巨大な欲望体であり、世界はエロティックに迫り来るものでした。瞬間に自らの欲望を見出し、ラディカルに「写真とは何か」を問い続ける森山大道の軌跡を106点の写真で綴った一冊です。

購入ご希望の方は、当ギャラリーへご連絡ください。

「1965~」森山大道

出版

: 916Press & 赤々舎

価格

: ¥3,465(税込)

To coincide with the opening of Daido Moriyama’s photography exhibition “1965~,” the photography book Daido Moriyama is now available. For Moriyama, the city was a single vast object of desire, and the world something that loomed erotically. This catalogue contains 106 pictures that trace the career of a photographer who sought in each moment his own desire and never ceased questioning in a radical manner “What is photography?”

Daido Moriyama: 1965~

Published by 916Press & Akaaka

¥3,465( with Tax )

overview

1965~

森山 大道

会期

: 6月1日土曜日 - 7月20日土曜日

開館時間

: 平日 11:00 - 20:00 / 土曜・祝日 11:00 - 18:30

定休

: 日曜・月曜日(7月15日を除く)

入場料

: 800円 (18歳以上、Gallery916及び916small)

作品のご購入に関してはギャラリーにお問い合わせください。

TEL:

03-5403-9161

/ FAX:

03-5403-9162

MAIL:

mail[a]gallery916.com

1965~

Daido Moriyama

Date

: 1 June, 2013 - 20 July, 2013

Time

: Weekday 11:00 - 20:00 / Saturdays and Holidays 11:00 - 18:30

Closed

: Sundays and Mondays (Except for 2013.7.15)

Daido Moriyama, the photographs

For enquiries regarding

the purchase of the photographs,

please contact the gallery.

TEL:

+81-(3)-5403-9161

/ FAX:

+81-(3)-5403-9162

MAIL:

mail[a]gallery916.com